Prologue One

At our 2015 IAME (International Association of Maritime Economists) conference in Kuala Lumpur, I organized a discussion session on the “impact of our work”. I wanted to discuss and promote ways to ensure that our academic research had an impact in the real world. Do businesses and policy makers actually make use of our papers?

At our 2015 IAME (International Association of Maritime Economists) conference in Kuala Lumpur, I organized a discussion session on the “impact of our work”. I wanted to discuss and promote ways to ensure that our academic research had an impact in the real world. Do businesses and policy makers actually make use of our papers?

For my work at UNCTAD, I have to report annually on indicators of achievement that go beyond “outputs”. Of course outputs (e.g. seminars, studies, statistics) are also counted, but a next step is to measure if our outputs are also used and appreciated. So we count the number of downloads, send out readership surveys, and collect evaluation sheets from workshop participants. But this does not guarantee an impact either. Therefore, as much as possible, we have to show that governments have implemented a policy, improved the performance of a Customs administration, or modernized a port authority “with the help of UNCTAD”. Fortunately, we are usually able to identify such cases, thanks to our direct engagement with national administrations and ministries. In addition, we are required to track existing benchmarks of trade efficiency, such as the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI), the Doing Business (DB) indicator, or UNCTAD’s Liner Shipping Connectivity Index (LSCI), and somehow show that such indices improved from one year to another as a result of our work. The attribution is impossible to prove, but I appreciate that we should at least try.

With these types of examples in mind, at our IAME 2015 conference in Kuala Lumpur, I had thus invited to a special session on the “impact” of the research we publish in our associated journals MEL and MPM, present at our IAME conferences, or dissiminate in our on-line magazine The Maritime Economist.

Well, frankly, the session didn’t quite work out as I had hoped. The discussions were lively and interesting, and we had a good attendance of the session. But after introductions by Hercules Haralambides and myself with some initial ideas on how to achieve an impact in real life, the discussions for most of the 90 minutes regressed to what really matters to the (academic) maritime economist: How can I publish in a high-impact factor journal? Because publishing in high-impact journals helps me to get tenure. Because my financial compensation may vary depending on the number of papers published in indexed journals. Because the impact factor is part of a “vicious cycle“, at the core of the “scientific ecosystem“. It appeared that researchers think that their “impact” is measured by their “impact factor”.

Well, frankly, the session didn’t quite work out as I had hoped. The discussions were lively and interesting, and we had a good attendance of the session. But after introductions by Hercules Haralambides and myself with some initial ideas on how to achieve an impact in real life, the discussions for most of the 90 minutes regressed to what really matters to the (academic) maritime economist: How can I publish in a high-impact factor journal? Because publishing in high-impact journals helps me to get tenure. Because my financial compensation may vary depending on the number of papers published in indexed journals. Because the impact factor is part of a “vicious cycle“, at the core of the “scientific ecosystem“. It appeared that researchers think that their “impact” is measured by their “impact factor”.

Prologue Two

A couple of years later, I received an invitation from a renowned publisher to select and publish the 30 papers in Maritime Economics with the highest impact. I enthusiastically accepted, started writing an introductory paper, and began thinking of how to select the papers.

Of course, the “impact factor” had to be part of the equation. For an academic, being quoted in the relevant literature is a valid indicator of the influence his or her work has on future academic research. But I also wanted to add another dimension, which was to see if the research is being applied in the real world. The latter is more difficult to capture, but at least I wanted to give it a try.

Once I had compiled my list, I sent it to the publisher. The counterpart was very helpful in identifying the journals and books and initiating contact with the publishers of the original papers. There was just one catch: There were too many papers from one publisher (Taylor and Francis), as there was a maximum percentage that could come from this publisher. Taylor and Francis is the publisher of our IAME associated journal MPM, founded even before IAME, with eight issues published per year. It should not come as a surprise that a certain percentage of my selection of the “most influential” papers comes from MPM and other journals and books of the same publisher. In total, T&F publishes 48 journals with maritime or marine in their title; as well as numerous relevant books such as Costas Grammenos’ Handbook of Maritime Economics and Logistics (Grammenos, 2012). It meant that my “selection” would not be my free choice of papers – and my enthusiasm for the book project waned. No hard feelings against the publisher (it is the system, isn’t it?), just as I trust this publisher can’t object that under the circumstances I choose other channels for presenting my thoughts.

I also kept reading about the publishing business model. I continued to review papers free of charge. I saw my budget to purchase books and journals being reduced while prices continued to go up. And my enthusiasm waned further.

And then I got another invitation, from another publisher. This time to write a contribution to some encyclopedia on transportation. In fact, I got two invitations to write two papers on different topics related to maritime economics for this encyclopaedia. But then came the conditions: A payment of 100$ (no, not per hour, but for each original article) – and the privilege that I could thereafter buy the books to which I contributed at half price. I am sorry, but you must be joking.

These experiences finally tilted my enthusiasm for the book project, and the publisher and I agreed that I could withdraw. I decided that I would aim at publishing as much as possible under open access conditions. Just as all our work at UNCTAD is open access – paid for by your taxes, thank you very much.

So here comes one such “open-access” blog post. Thinking aloud about long term trends in maritime transport, and a very subjective list of the 50 most influential papers that have accompanied those trends over the last decades. It is not peer reviewed, nor edited, and if I cite you in it, it doesn’t count for your “impact factor”. I trust you may still enjoy reading it – at least I had fun during its writing.

Introduction

Two thirds of our earth are covered by the oceans, and 80% of global trade by volume is transported by ships. A typical maritime transport operation easily involves inputs from more than a dozen countries. The ship may be built in the Republic of Korea, financed by a German bank, flying the flag of Panama, manned by Philippine seafarers who are employed via a crewing agent from Cyprus. The beneficial owner could be a Greek national living in London, who charters her ship out to Danish liner company. She may insure her ship in the United Kingdom and have it classed in Norway. The ship could be transporting containers that are built in Shanghai, with cargo exported from Japan to the Netherlands, arranged by a freight forwarder from Switzerland. On its journey, the ship may bunker fuel in Singapore, and the container could be transhipped in Djibouti, in a terminal that is (sorry: was) operated by Dubai Ports. At the end of its life, this ship will likely be scrapped on a beach in Bangladesh or India.

Studying and living the economics of this most globalized of businesses is a fascinating and rewarding task. I have been privileged to work on port and shipping issues with colleagues at the IMO in London, UN-ECLAC in Santiago de Chile, and at UNCTAD in Geneva, most recently preparing the 50th anniversary issue of the UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport. As a member of IAME and on the boards of its two associated journals MEL and MPM, I have benefited from the research and insights of the many friends and colleagues who study and publish on a wide range of topics in the field of maritime economics. Earlier in life, I had already experienced the ups and downs of the shipping cycle thanks to our family company “Hoffmann Shipping” – a tween-decker deployed in tramp shipping, with a Polish crew and flagged in Antigua and Barbuda. In 1985, I got my Seefahrtbuch at the local ITF affiliated trade union, and we lived through the difficult times of flagging out, renegotiating loans, complying with flag and port state regulations, and contracting brokers, insurances and crewing agents.

Studying and living the economics of this most globalized of businesses is a fascinating and rewarding task. I have been privileged to work on port and shipping issues with colleagues at the IMO in London, UN-ECLAC in Santiago de Chile, and at UNCTAD in Geneva, most recently preparing the 50th anniversary issue of the UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport. As a member of IAME and on the boards of its two associated journals MEL and MPM, I have benefited from the research and insights of the many friends and colleagues who study and publish on a wide range of topics in the field of maritime economics. Earlier in life, I had already experienced the ups and downs of the shipping cycle thanks to our family company “Hoffmann Shipping” – a tween-decker deployed in tramp shipping, with a Polish crew and flagged in Antigua and Barbuda. In 1985, I got my Seefahrtbuch at the local ITF affiliated trade union, and we lived through the difficult times of flagging out, renegotiating loans, complying with flag and port state regulations, and contracting brokers, insurances and crewing agents.

This blog post is divided into two parts.

- First, I will look at major trends in international maritime transport over the last three decades. I follow a classical approach of economics, looking at demand, supply, and markets, as well as the ports through which shipping services connect with the hinterland. This part benefits from and builds upon our work at UNCTAD (with many thanks to colleagues and co-authors), as well as some earlier blog posts.

- The second part will present a list of 50 papers which I consider the most influential papers that have accompanied the previously discussed long-term trends. Here I thank my friends and colleagues at IAME for 20 years of cooperation since I joined the association, and I hope to encourage further discussion on the “impact” of our work.

Part 1 – Demand, supply, and markets: Economic trends in maritime transport

Demand

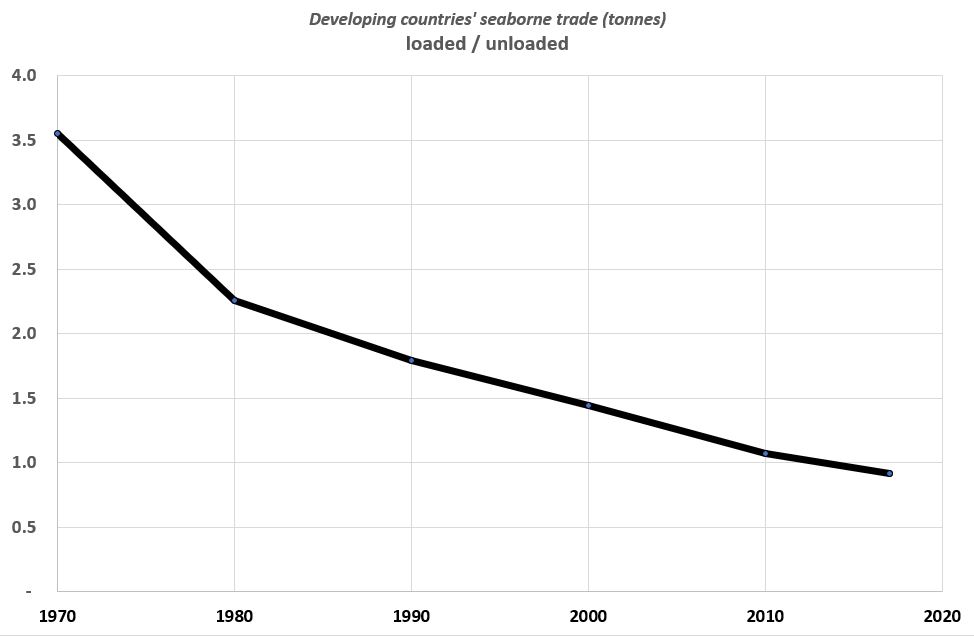

The geography of maritime trade has seen fundamental changes during the last decades. In 1970, developing countries were mere providers of raw materials that were exported to the industrialized countries, while the latter exported manufactured goods to the “South”. Taking data from seaborne trade of goods loaded and un-loaded, in 1970, developing countries accounted for 63.3% of goods loaded for exports, against only 17.8% of goods unloaded as imports (Figure 1). In terms of volume, they thus head a huge trade surplus. However, exported volumes were largely limited to low-value raw materials and primary products, such as iron ore, oil, coal or soya. The imports, on the other hand, were high-value manufactured goods produced and exported by the developed industrialized countries.

Figure 1. The chainging geography of trade. Source for the data: http://stats.unctad.org/seabornetrade

Today, the picture is very different. In 2016, developing countries in fact imported a higher volume (64%) of seaborne trade than they exported (59%) (UNCTAD, 2017). Thanks mostly to China, but also trends in other emerging economies, developing countries are no longer mere providers of raw materials, but participate in the globalised production of goods and services. Their demand for seaborne trade accordingly covers imports and exports of intermediate and manufactured goods from all regions of the world.[1]

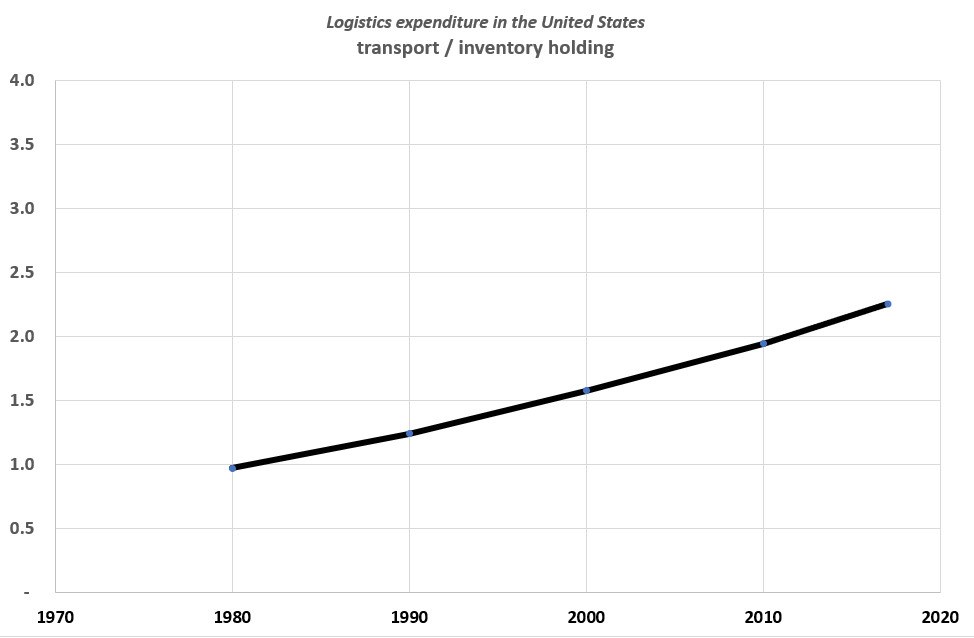

A second major trend in the demand for maritime transport is its use within global value chains. There is more trade in intermediate goods than in raw materials or finished goods, exemplifying the globalized production of goods and services. This trend is also reflected in a shift in the components of logistics expenditures.

In the United States, for example, we see a growing share of expenditures in transport, while the share of inventory holding is going down. Still in 1980, the US economy would spend more on inventory holding than on transport within total logistics costs, while in 2017 the share of transport expenditure was more than double that on inventory holding (Figure 2). This does not mean that transport has become more expensive. Rather on the contrary – as freight costs have gone down, and factories require more frequent and faster deliveries to support their global value chains and Just in Time (JIT) deliveries, businesses purchase more transport, and reduce their expenditures on inventory holdings.[2]

Figure 2. Spending money on transport instead of inventory holding. Source for the data: ATKearney, “State of Logistics Report”, various issues. https://www.atkearney.com/transportation-travel/state-of-logistics-report

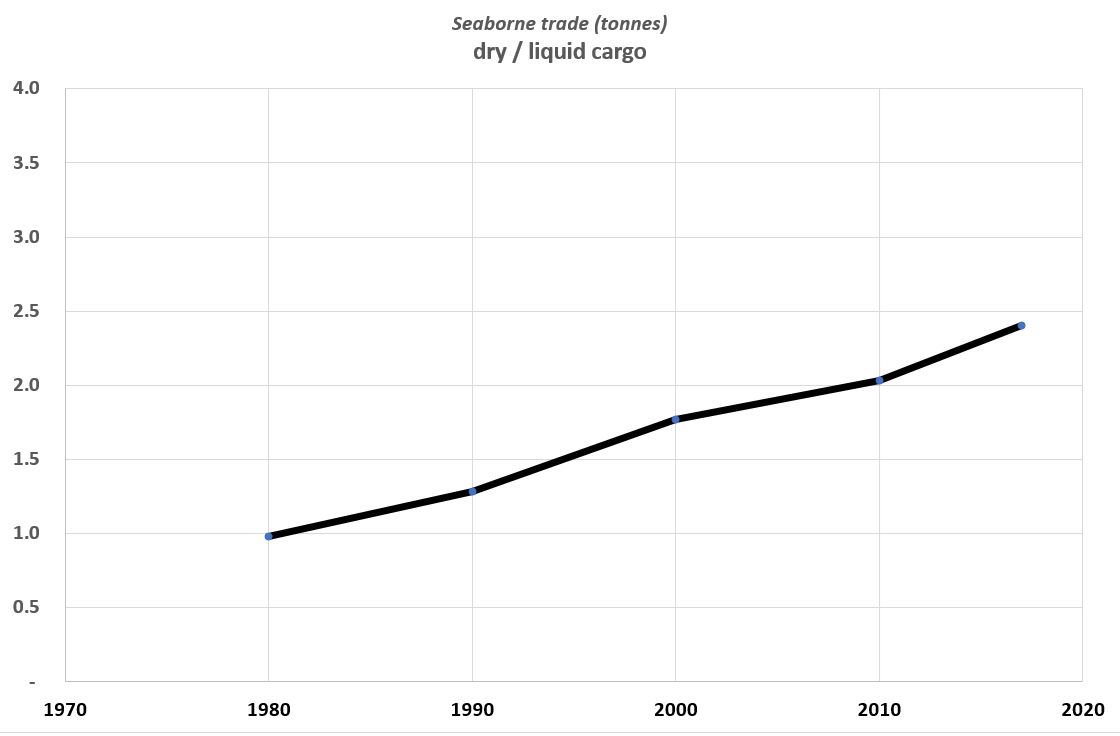

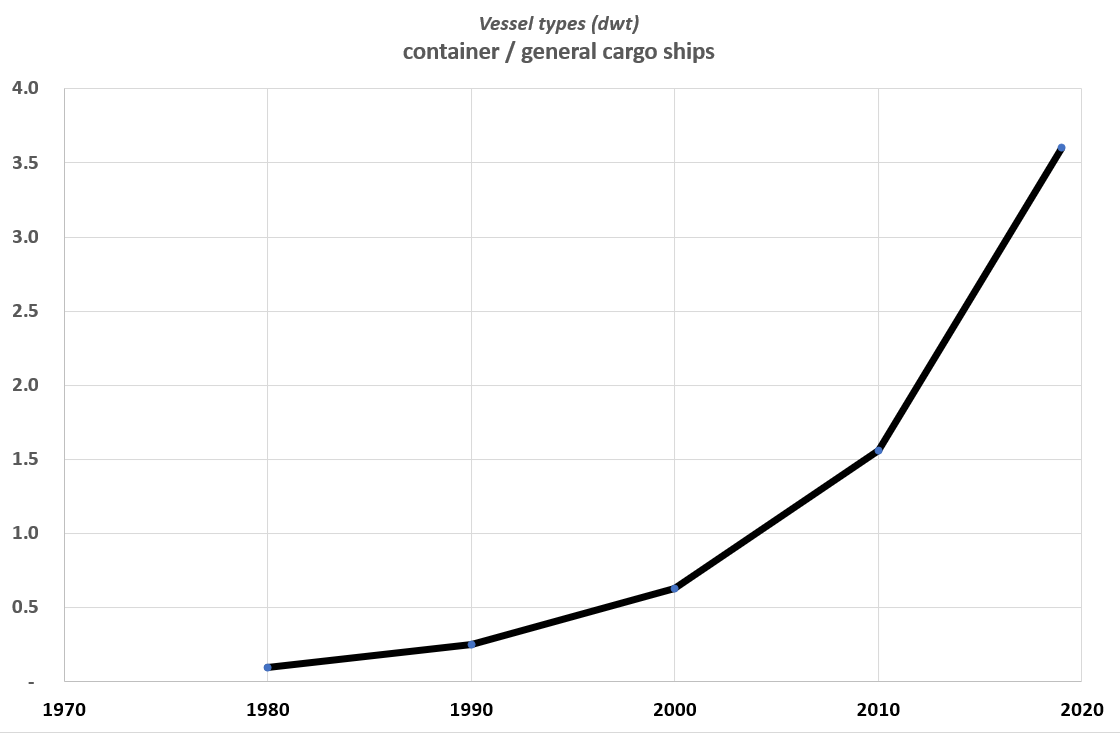

A third trend on the demand side is a shift in the types of cargo. There is a growing share of dry cargo as compared to liquid cargo (Figure 3), and the dry cargo is increasingly being containerized. In terms of value, today more than half of international seaborne trade is containerized, and container ships are largely replacing the traditional general cargo vessels (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The changing mix of traded commodities. Source for the data: http://stats.unctad.org/seabornetrade

Figure 4. Containerization. Source for the data: http://stats.unctad.org/fleet

The sea-container was invented by a provider of transport services – the trucker Malcolm McLean in 1956 – so we could also consider containerization as a dimension of the supply side of shipping. At the same time, the tremendous growth of container shipping is really a reflection of the demand for low-cost, frequent, and reliable door-to-door transport. As we will see, a lot of the research in maritime economics is about container shipping and terminal operations.[3]

Supply

Just as we observe globalized production of goods on the demand-side of shipping, we also observe the globalized production of the shipping services. Above, I already mentioned the typical case, where a single maritime transport operation may involve suppliers from more than a dozen countries. The nationality of the ship owner is less and less often the same as the flag his ship flies (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The trend of flagging out. Source for the data: www.unctad.org/RMT

As of January 2019, the top five ship owners in terms of cargo carrying capacity (dwt) are Greece, China (including Hong Kong), Japan, Singapore, and Germany; together these five countries have a market share of 55.9 per cent of dwt. The five largest flag registries are Panama, Marshall Islands, Liberia, Hong Kong (China SAR) and Singapore. Together they have a market share of 57.5 per cent. Three countries (China, Republic of Korea, and Japan) constructed 90.2 per cent of world gross tonnage in 2018, and three countries (Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan) together accounted for 91.1 per cent of ship scrapping in 2018 (source: UNCTAD, based on data provided by Clarksons Research).

We thus no longer have “maritime nations” that are supplying maritime transport with their own nationally built, flagged and manned vessels, but the provision of transport by sea has become a global value chain with inputs from many different countries. As countries specialize in different maritime sub-sectors, we also observe a process of concentration. In most businesses, an ever-smaller number of companies from only a few countries in each segment has remained in business. In an earlier article in The Maritime Economist I had already presented the UNCTAD Maritime Country Profiles that illustrate each country’s participation in different maritime businesses.[4]

Markets

The above-described trends in demand and supply have allowed for gains in efficiencies and economies of scale. In today’s mostly liberalized shipping markets this has resulted in very low transport costs to the shipper. However, as countries have specialized and companies merged and formed alliances, the ensuing process of consolidation has – at least in some segments – led to increasingly oligopolistic market structures.

For the case of container shipping, when working for UN-ECLAC in Santiago de Chile, I had been tasked with researching the causes and impacts of the process of concentration in this sector. At that time, in 1997, the first post-panamax container ships had just entered service, and shippers, ports and regional shipping lines were concerned about the mergers and alliances among liner companies. My resulting study was published in 1998 under the title “Concentration in liner shipping: its causes and impacts for ports and shipping services in developing regions”.

The study pointed out that “The size of the largest container ships has almost tripled within the last two decades.” The largest ship at that time had a capacity of 6600 TEU – today’s ships are three times larger. The study also highlighted that “The top 20 carriers now control more than half of the world’s container slot capacity” – today, beginning of 2019, just the top 10 carriers control more than 91% of the total capacity offered on the deep-sea market (data provided by MDST). As regards consortia and alliances, the 1998 study said that “The largest ten groupings now control about two thirds of the world’s container slot capacity” – today, just three major alliances are left, and they control more than 80 per cent of capacity on most major routes.

A major underlying cause for the process of concentration, in my view, continues to be the technological change towards higher fixed costs against lower variable costs. Still today, “new technologies lead to a changing cost function. In ports and shipping, these changes include an increased proportion of fixed costs as compared to variable costs. This shift of the relation fixed costs/variable costs leads to increased scale economies. This, in turn, implies larger optimum company sizes and thus leads to a reduction of the number of players in the long-term market equilibrium” (Hoffmann, 1998). Twenty years later, we continue to see a reduction of the number of players, with the insolvency of Hanjin Shipping and mergers among various liner companies.

In the 1998 study, I had presented a “generally positive picture” of the sector’s level of competition: “On a global scale, there are now fewer operators than in the past, but on most individual trade routes the number of lines competing for cargo has actually increased. For example, Asian lines have entered the North Atlantic trade, east-west lines are entering north-south markets and the feeder services of large lines are competing with traditional regional lines.” And overall, in the ensuing twenty years, freight costs did decline, and maritime connectivity increased.

Today, however, consolidation has reached levels that merit a renewed look at its implications and possible policy responses. On a number of routes concentration has led to oligopolistic or even monopolistic markets, with more than one quarter of countries being serviced by only one to four container carriers. If there is not enough demand to attract frequent and competing shipping services, trading becomes costly and not competitive, and volumes drop even further.

On the one hand, global trade benefits from low freight costs and improved shipping connectivity that result from economies of scale and technological advances, yet on the other hand the mergers among shipping lines and their investments in ever larger ships also imply serious challenges to smaller trading nations and their seaports. Ships get bigger, while the number of carriers that provide services from and to the average country goes down. Concretely, between 2004 and 2019, the average size of the largest ships deployed per country increased by 169 per cent, while the average number of service providers per country decreased by 32 per cent. As companies left the market and the total volume continued to grow, the transport capacity provided per carrier grew 3-fold during this period. challenge for policy makers is to ensure that the benefits of lower costs and improved connectivity are passed on to the smaller shippers and ports.

The largest containerships delivered this year have set new records, with a carrying capacity of more than 23 000 standard containers. While these mega containerships have been in the news given the associated challenges for ports in Europe and Asia, thanks to the cascading effect, it is in fact the smaller ports in many developing countries that are affected the most.

Less than 20 per cent of coastal country pairs have a direct bilateral maritime connection, meaning that containerized goods can be transported between a country of origin and a destination without the need for trans-shipment. More than 80 per cent of country pairs do not have a direct connection, which is empirically associated with higher transport costs. This includes large trading nations that lie across the same ocean such as, for example, Brazil and Nigeria. An interesting question for trade and transport analysts is whether the absence of direct connections between the two countries results from the limited demand from trade, or whether limited bilateral trade is a consequence of these two countries not being well connected. As discussed in UNCTAD (2017), there is evidence for both.

Cui Bono? It takes time to plan, order and build ships, and today’s oversupply of tonnage is the result of past investment decisions against slower than expected demand growth, supported by cheap financing and low new building prices. Carriers react to the oversupply with what they consider their own best interest: To reduce their unit costs, they invest even more in bigger and more fuel-efficient new ships. Confronted with the resulting over-supply of transport capacity, in the short term, carriers offer their services below their long-term average costs – as long as the operating costs are covered.

The negative impacts of this behaviour are three-fold:

- When a company replaces old ships with new ones, the old ones do not exit the market. The overcapacity persists, as of the containership fleet is too young to be demolished and old ships are sold on the second-hand market. In the end all carriers are confronted with the historically low freight rates. Some – like Hanjin in 2016 – couldn’t cope any longer and filed for bankruptcy, while other companies from Asia and South America have over the last years been taken over by European shipping lines.

- The larger ships help cut unit costs for ocean shipping, but the total system costs go up, as the ports, the intermodal transport providers and the shippers will incur additional expenses to cope with rising vessel sizes. This not only applies to those ports in Europe and Asia which accommodate the largest ships, but also to smaller ports in many developing countries due to the cascading effect.

- As ships get bigger and carriers need to expand to fill their ships, there is space for fewer carriers in individual markets. We observe a continued process of concentration. There is a growing danger of a proliferation of oligopolistic market structures in various trade routes, especially in smaller developing countries.

The typical shipping cycle over the last two centuries lasted between 3.5 and 7 years. For more than a decade now, however, container ships have kept growing in size, which has encouraged ship owners to continue their investments in ever bigger new ships for too long. The continued expansion has led to a long period of low and volatile freight rates. Until we have reached a new plateau in vessel sizes, this situation is unlikely to change.[5]

Ports

Seaports connect maritime transport services to each-other through transhipment, and they connect ocean shipping to in-land transport services, including trucking, railways, air-lines, pipelines and in-land waterways. They are commonly included in the scope of “maritime economics” in text books, specialized journals and the ambit of IAME conferences.

Seaports development is closely linked to structural changes in shipping and containerization. Most seaports are today operated by private companies, often under concession contracts, while historically they were mostly government run. The public sector retains an important role as regulator and planner for infrastructure investments.

Ports have become more and more automated and are no longer seen as a primary source for employment. Rather, they are important to provide cost-efficient, fast and reliable services, so that employment can be generated in the import-export sectors that depend on the seaports.

Technological developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) are giving rise to fascinating new challenges and opportunities to seaports. Current warehouse operations that are characterised by fully automated movements, robots, and inter-connected IT systems offer a glimpse of how the future of seaports may look like. Driver-less transport, combined with full tracking of cargo, containers and vehicles, connected to global information systems, will be planned and organized by AI. Who will control this wealth of data and information? Should policy makers encourage vertical integration of port and shipping businesses to make the most efficient use of these opportunities, at the risk of collusion or abuses of market consolidation? And if we go one step further, allowing AI to take control, what are the goals and values that should be programmed into these AI systems?

We do not know what technologies will be available to seaports in coming generations. When setting the legal and regulatory framework under which seaports operate, regulators should not be too prescriptive as regards specific technologies. By way of example, when the negotiations on trade facilitation started at the World Trade Organization in 2004, negotiators from many developing countries were reluctant to commit their countries to “publish information on the internet”. Developing countries lacked the capacity, they said, and such publication implied the need to invest in costly IT solutions. One decade later, when the negotiations were concluded, this was much less of an issue. By the same token, the concept of “copies” versus “originals” will become obsolete as processes focus on data rather than on documents. And as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) manual for the Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL) is being revised, references to the electronic submission of data are being deleted – not because data should not be transmitted electronically, but rather because alternative transmissions are not even considered any longer.

Decisions pertaining to the above-mentioned technologies will increasingly involve AI, and AI will learn and adapt exponentially faster to new challenges and technologies than humans, as newly acquired knowledge is immediately passed on to fellow AI-endowed units

In the past, a typical introductory question at courses for port managers was “Who is the port’s client: the shipper or the carrier?” The correct answer was that the port provides services to both: The cargo and the vessels. Today, a third client needs to be added: the tenant, i.e. the terminal operating company that has a concession from the land-lord port authority.

In this setting, ports are confronted with an increasingly competitive environment. Global value chains require ever more reliable and fast trade transactions, and, at the same time, inter-port competition is on the rise, as improved intermodal connections, transhipment and transit make it easier for shippers to switch ports. On the carriers’ side, the process of consolidation through mergers and alliances has significantly strengthened their bargaining power vis-à-vis the port.

To make matters worse for the ports, the process of consolidation has not stopped at horizontal mergers and alliances, but increasingly also involves vertical integration. If a terminal operator is part of a carrier’s group holding, the associated terminal may be the natural choice as port of call. Example: As Maersk acquired Hamburg Süd, the latter’s services can be expected to switch from their previously used terminals in Buenos Aires and Callao to the ones operated by APM – which belongs to the same group as Maersk.

Thanks to the global liner shipping network and continued investments by the carriers, freight rates have remained low and shippers can basically trade across the entire globe. However, cost reductions on the shipping side are not equally matched with reduction in hinterland transport costs and port handling charges. The growing vessel sizes have led to additional costs due to higher peak demand. Ports are under pressure to dredge, expand yards and invest in ever larger ship-to-shore container cranes, often without any additional cargo throughput. The resulting total door-to-door logistics costs thus no longer benefit from further deployment of mega container ships.

Port operations have significantly improved since the 1990s, when in most parts of the world terminal operations were concessioned under a land-lord scheme. Today, many of the first concessions come to an end, and port authorities need to find new tenants or renegotiate existing concessions. Classical criteria for assigning a concession on the basis of, for example, the lowest cargo handling charges may no longer be the best option, if the client is de facto the same company as the terminal operator. In sum, port authorities are confronted with a much more complex scenario, compared to when the first terminals were handed over to private operators.

Finally, ports are also confronted with additional demands as regards the sustainability of their operations. Ports need to minimise social and environmental externalities. Many port cities are among the most polluted places to live, as ships burn heavy oil, produce noise, and cause traffic congestions. Port cities need to adopt long term perspectives for their waterfront properties – and using prime land for cargo handling may not always be the best option. Ports also need to be resilient in the face of disruptions and damages caused by natural disasters and climate change impacts.[6]

Part 2 – Research in maritime economics: The 50 most influential papers

Above, I have discussed what I consider major trends in the maritime economy over the last decades. With this in mind, I now come to the corresponding research on maritime economics. Which are the 50 most influential papers that have accompanied these trends?

Some selection criteria

I started out with a list of papers based on how often they were cited, making use of Harzing’s Publish or Perish tool. I searched for “Maritime Economics” and some related terms, and downloaded a list of the top 150 papers, books and book-chapters. I then went through them and added some subjective bias to come up with my own list of the top 50.

Some papers on my list may not be among the top 50 in terms of citations, but they represent authors and lines of thought that have had a strong bearing on business and policy making. For example, while Juhel (2001) is not among the 50 most cited, the World Bank Port Reform Toolkit has had a significant influence on port concessions around the world, and Marc Juhel was the driving force behind the toolkit. Martin Stopford is best known for his text book Maritime Economics, which is a core reference for every researcher and student of Maritime Economics, while his papers, such as Stopford (2002), might not be among the 50 most cited. Some others, such as Bernhofen et al. (2016) and Hummels (1999), might not consider themselves maritime economists, but their papers have been highly influential, also in the field of maritime economics.

If similar papers from the same authors appeared among the top 50, I took only one, which appeared more fundamental. Some other papers appeared formally among the top 50 under the search term “maritime economics”, but I felt they were not sufficiently focused on this topic. Among the topics within the field of Maritime Economics, there are more papers on ports than, for example, in shipping finance, and as such port related papers are also more likely be cited by other port related papers. I have taken this into account and swapped some of the less-often cited port papers for papers on other issues that might otherwise not have made the cut.

Beyond the papers, let me also mention some of the more influential books. The by far most often quoted book in Maritime Economics is Stopford (2009). The book, already in its third edition (and Martin is working on the next one), is used in most classes for students of maritime transport issues and thus has a long-term influence on the thinking in our field. Other frequently quoted books are Button (2010), Cullinane (2011), Goss (1977), Grammenos (2002) and Grammenos (2012).

For a thorough quantitative and peer reviewed analysis of the top 50 authors, affiliations, and countries in the broader maritime transportation field, see the excellent and peer reviewed paper by Chang et al. (2018). Their analysis covers articles published in 65 journals in maritime and transportation. They use three indicators for their ranking: number of papers, the weighted score that reflects the contribution of the authors, and the impact score which considers the impact factor. The authors also look into trends over five-year intervals.

Introspective: What is my impact?

As regards my own “impact”, the co-authored paper Sánchez et al. (2003) on determinants of internaional transport costs is cited 296 times and thus makes the cut into the 50 most cited in the field. It builds on earlier work done at UN-ECLAC (Hoffmann, 2002), followed by Wilmsmeier et al. (2006) and Wilmsmeier and Hoffmann (2008), among others. Another stream of my work has been on the globalization of shipping, including Kumar and Hoffmann (2002), Hoffmann (2003), Hoffmann et al. (2004), and subsequently the annual chapters to which I contributed for UNCTAD’s Review of Maritime Transport. More recently, I have worked on shipping connectivity ((Hoffmann, 2012; Fugazza et al., 2013; Fugazza and Hoffmann, 2017; Hoffmann et al., 2017; and Hoffmann et al, 2019), building on the earlier work on transport costs, in combination with work on ports (Hoffmann, 2000) and container shipping (Hoffmann, 1998).

Beyond papers and reports, probably the stronger “impact” of my work comes from the production of publicly available information and statistics by the United Nations, to be used free of charge by policy makers and researchers. At UN-ECLAC, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we developed a regional maritime country profile, as well as a database on the transport costs of Latin American countries, both of which are still alive and being updated. At UNCTAD, we produce a growing set of maritime statistics, indices of liner shipping connectivity, and maritime country profiles. This work is complemented by extensive technical assistance in transport and trade facilitation. Our advisory services and technical cooperation with UNCTAD’s members benefit from our maritime research and data when we work, for example, on maritime trade scenarios, port training, competition, shipping policies, trade and transport facilitation, port performance indicators, or CO2 emissions from shipping.

Beyond papers and reports, probably the stronger “impact” of my work comes from the production of publicly available information and statistics by the United Nations, to be used free of charge by policy makers and researchers. At UN-ECLAC, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we developed a regional maritime country profile, as well as a database on the transport costs of Latin American countries, both of which are still alive and being updated. At UNCTAD, we produce a growing set of maritime statistics, indices of liner shipping connectivity, and maritime country profiles. This work is complemented by extensive technical assistance in transport and trade facilitation. Our advisory services and technical cooperation with UNCTAD’s members benefit from our maritime research and data when we work, for example, on maritime trade scenarios, port training, competition, shipping policies, trade and transport facilitation, port performance indicators, or CO2 emissions from shipping.

Papers and impact

In the end, the “impact” of a researcher’s work will come from a combination of how often his or her research is being read, and its application in real life. Most IAME members are not pure academics but often also develop and implement projects or do consultancy services.

If a paper is frequently cited in the literature this is a good first indicator for being influential. But it is the subsequent use by business or policy makers that will ultimately define a paper’s “impact”.

So, finally, here comes my proposed list of the most influential papers in maritime economics, combining the objective criteria of number of citations with some subjective criteria disucced above. They are in alphabetical order, grouped into six overlapping topical areas.

A. Shipping history and major trends

Papers that cover a wide range of long-term developments and historical trends.

- Bernhofen, D.M., El-Sahli, Z., Kneller, R., 2016. Estimating the effects of the container revolution on world trade. Int. Econ. 98, 36–50.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.09.001 - Goss, R.O., 1990. Economic policies and seaports: The economic functions of seaports. Policy Manag. 17, 207–219.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839000000028 - Heaver, T., Meersman, H., Moglia, F., Van De Voorde, E., 2000. Do mergers and alliances influence European shipping and port competition? Marit. Policy Manag. 27, 363–373.

https://doi.org/10.1080/030888300416559 - Heaver, T.D., 2002. The Evolving Roles of Shipping Lines in International Logistics. J. Marit. Econ. 4, 210–230.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100042 - Liu, M., Kronbak, J., 2010. The potential economic viability of using the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as an alternative route between Asia and Europe. J. Transp. Geogr., Tourism and climate change 18, 434–444.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.08.004 - Psaraftis, H.N., Kontovas, C.A., 2009. CO2 emission statistics for the world commercial fleet. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 8, 1–25.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03195150 - Slack, B., Comtois, C., McCalla, R., 2002. Strategic alliances in the container shipping industry: a global perspective. Policy Manag. 29, 65–76.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830110063694 - Slack, B., Frémont, A., 2005. Transformation of port terminal operations: from the local to the global. Rev. 25, 117–130.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0144164042000206051 - Sletmo, G.K., 2001. The End of National Shipping Policy? A Historical Perspective on Shipping Policy in a Global Economy. J. Marit. Econ. 3, 333–350.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100024

B. Demand: Maritime trade and networks

These papers look into seaborne trade, trade flows and networks.

- Carbone, V., Martino, M.D., 2003. The changing role of ports in supply-chain management: an empirical analysis. Policy Manag. 30, 305–320.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000145618 - Ducruet, C., Notteboom, T., 2012. The worldwide maritime network of container shipping: spatial structure and regional dynamics. Netw. 12, 395–423.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00355.x - Kaluza, P., Kölzsch, A., Gastner, M.T., Blasius, B., 2010. The complex network of global cargo ship movements. R. Soc. Interface 7, 1093–1103.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2009.0495 - Lirn, T.C., Thanopoulou, H.A., Beynon, M.J., Beresford, A.K.C., 2004. An Application of AHP on Transhipment Port Selection: A Global Perspective. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 70–91.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100093 - Notteboom, T.E., Vernimmen, B., 2009. The effect of high fuel costs on liner service configuration in container shipping. Transp. Geogr. 17, 325–337.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.05.003 - Slack, B., 1985. Containerization, inter-port competition, and port selection. Marit. Policy Manag. 12, 293–303.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088838500000043

C. Supply: Maritime business and clusters

Papers that focus on port and shipping services, businesses and clusters.

- Cullinane, K., Khanna, M., 2000. Economies of scale in large containerships: optimal size and geographical implications. J. Transp. Geogr. 8, 181–195.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(00)00010-7 - Heaver, T., Meersman, H., Van De Voorde, E., 2001. Co-operation and competition in international container transport: strategies for ports. Policy Manag. 28, 293–305.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830110055693 - Langen, P.W. de, 2002. Clustering and performance: the case of maritime clustering in The Netherlands. Policy Manag. 29, 209–221.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830210132605 - Sys, C., 2009. Is the container liner shipping industry an oligopoly? Policy, SI: TBGS 16, 259–270.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2009.08.003

D. Prices: Freight rates, port charges and costs

Papers that discuss transport costs and prices, including for shipping, i.e. freight rates, and for ports, i.e. port pricing issues.

- Adland, R., Cullinane, K., 2006. The non-linear dynamics of spot freight rates in tanker markets. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 42, 211–224.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2004.12.001 - Batchelor, R., Alizadeh, A., Visvikis, I., 2007. Forecasting spot and forward prices in the international freight market. Int. J. Forecast. 23, 101–114.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.07.004 - Clark, X., Dollar, D., Micco, A., 2004. Port Efficiency, Maritime Transport Costs and Bilateral Trade (NBER Working Paper No. 10353). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/nbrnberwo/10353.htm - Haralambides, H.E., 2002. Competition, Excess Capacity, and the Pricing of Port Infrastructure. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 4, 323–347.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100053 - Hummels, D., 2007. Transportation costs and international trade in the second era of globalization. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 131–154.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.21.3.131 - Kavussanos, M.G., Visvikis, I.D., 2004. Market interactions in returns and volatilities between spot and forward shipping freight markets. J. Bank. Finance 28, 2015–2049.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2003.07.004 - Sánchez, R.J., Hoffmann, J., Micco, A., Pizzolitto, G.V., Sgut, M., Wilmsmeier, G., 2003. Port Efficiency and International Trade: Port Efficiency as a Determinant of Maritime Transport Costs. Econ. 38 Logist. 5, 199–218.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100073

E. Ports and intermodal connections

The literature on seaports is particularly extensive within the broader field of Maritime Economics. It includes research on the ports’ hinterland connections.

- Baird, A.J., 2000. Port Privatisation: Objectives, Extent, Process, and the UK Experience. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 2, 177–194.

https://doi.org/10.1057/ijme.2000.16 - Brooks, M.R., Pallis, A.A., 2008. Assessing port governance models: process and performance components. Policy Manag. 35, 411–432.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830802215060 - Cullinane, K., Song, D.-W., 2002. Port privatization policy and practice. Rev. 22, 55–75.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640110042138 - Juhel, M.H., 2001. Globalisation, Privatisation and Restructuring of Ports. J. Marit. Econ. 3, 139–174.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100012 - Notteboom, T.E., Rodrigue, J.-P., 2005. Port regionalization: towards a new phase in port development. Marit. Policy Manag. 32, 297–313.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830500139885 - Notteboom, T.E., Winkelmans, W., 2001. Structural changes in logistics: how will port authorities face the challenge? Marit. Policy Manag. 28, 71–89.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830119197 - Robinson, R., 2002. Ports as elements in value-driven chain systems: the new paradigm. Marit. Policy Manag. 29, 241–255.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830210132623 - Rodrigue, J.-P., Notteboom, T., 2009. The terminalization of supply chains: reassessing the role of terminals in port/hinterland logistical relationships. Policy Manag. 36, 165–183.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830902861086 - Song, D.-W., 2003. Port co-opetition in concept and practice. Marit. Policy Manag. 30, 29–44.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000051612 - Tongzon, J., Heng, W., 2005. Port privatization, efficiency and competitiveness: Some empirical evidence from container ports (terminals). Res. Part Policy Pract. 39, 405–424.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.02.001 - Van Der Horst, M.R., De Langen, P.W., 2008. Coordination in Hinterland Transport Chains: A Major Challenge for the Seaport Community. Econ. 38 Logist. 10, 108–129.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100194 - Verhoeven, P., 2010. A review of port authority functions: towards a renaissance? Policy Manag. 37, 247–270.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088831003700645 - Wang, J.J., Ng, A.K.-Y., Olivier, D., 2004. Port governance in China: a review of policies in an era of internationalizing port management practices. Policy 11, 237–250.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2003.11.003

F. The efficiency of maritime transport

Finally, papers that look at the performance of port and shipping services, including its sustainability.

- Acciaro, M., Vanelslander, T., Sys, C., Ferrari, C., Roumboutsos, A., Giuliano, G., Lam, J.S.L., Kapros, S., 2014. Environmental sustainability in seaports: a framework for successful innovation. Marit. Policy Manag. 41, 480–500.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2014.932926 - Barros, C.P., Athanassiou, M., 2004. Efficiency in European Seaports with DEA: Evidence from Greece and Portugal. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 122–140.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100099 - Bichou, K., Gray, R., 2004. A logistics and supply chain management approach to port performance measurement. Policy Manag. 31, 47–67.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000174454 - Corbett, J.J., Wang, H., Winebrake, J.J., 2009. The effectiveness and costs of speed reductions on emissions from international shipping. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 14, 593–598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2009.08.005 - Cullinane, K., Wang, T.-F., Song, D.-W., Ji, P., 2006. The technical efficiency of container ports: Comparing data envelopment analysis and stochastic frontier analysis. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 40, 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.07.003

- Estache, A., González, M., Trujillo, L., 2002. Efficiency Gains from Port Reform and the Potential for Yardstick Competition: Lessons from Mexico. World Dev. 30, 545–560.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00129-2 - Imai, A., Nishimura, E., Papadimitriou, S., 2001. The dynamic berth allocation problem for a container port. Res. Part B Methodol. 35, 401–417.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-2615(99)00057-0 - Notteboom, T.E., 2006. The Time Factor in Liner Shipping Services. Econ. 38 Logist. 8, 19–39.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100148 - Park, R.-K., De, P., 2004. An Alternative Approach to Efficiency Measurement of Seaports. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 53–69.

https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100094 - Roll, Y., Hayuth, Y., 1993. Port performance comparison applying data envelopment analysis (DEA). Policy Manag. 20, 153–161.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839300000025 - Talley, W.K., 1994. Performance indicators and port performance evaluation – ProQuest. Logist. Transp. Rev. 30.

https://trid.trb.org/view/414803 - Tongzon, J.L., 1995. Determinants of port performance and efficiency. Res. Part Policy Pract. 29, 245–252.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0965-8564(94)00032-6

And yes, you have noticed it: The 50 papers have become 52. But then, there are three types of people on earth: Those that can count, and those that can’t.

And the future?

The main purpose of this blog post was the past:

- Long term trends over the last decades, and

- the maritime economics papers that have accompanied those trends.

For the future, I believe that the topics covered above will remain relevant, as the trends in demand, supply, markets and ports can be expected to continue to shape developments in maritime transport. Of growing relevance will be the role of digitalization and its implications for operations, competition, and the sustainability of port and shipping services.

Finally, shipping needs to become sustainable. Our industry will have to reduce its negative externalities – and this includes becoming carbon neutral. Yes, under most criteria, shipping causes less environmental and social damage than other modes of transport per tonne of cargo carried. Still, it moves 80% of global trade by volume, and even more if we count tonne-miles, so by it sheer volume it also has an important impact on the environment and communities. In my (personal) view, maritime economists have a crucial role to play to ensure that our sector assumes its responsibility and accepts the polluter pays principle, i.e. the internalization of externalities. An official IMO document of 1995, written by a young enthusiastic Junior Professional Officer working at Albert Embankment at that time, aimed at setting the scene (Figure 6).

Figure 6. “The internalization of costs”. Source: “Financial Matters. (c) Proposal for long-term financing of the Integrated Technical Co-operatoin Programme”. IMO, London, TC 41/7(c), 12 April 1995

Bibliography

In alphabetical order. Including those mentioned above, plus some more that I thought of interest. Formatting done by Zotero.

Acciaro, M., Vanelslander, T., Sys, C., Ferrari, C., Roumboutsos, A., Giuliano, G., Lam, J.S.L., Kapros, S., 2014. Environmental sustainability in seaports: a framework for successful innovation. Marit. Policy Manag. 41, 480–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2014.932926

Adland, R., Cullinane, K., 2006. The non-linear dynamics of spot freight rates in tanker markets. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 42, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2004.12.001

Baird, A.J., 2000. Port Privatisation: Objectives, Extent, Process, and the UK Experience. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 2, 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1057/ijme.2000.16

Barros, C.P., Athanassiou, M., 2004. Efficiency in European Seaports with DEA: Evidence from Greece and Portugal. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 122–140. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100099

Batchelor, R., Alizadeh, A., Visvikis, I., 2007. Forecasting spot and forward prices in the international freight market. Int. J. Forecast. 23, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.07.004

Bernhofen, D.M., El-Sahli, Z., Kneller, R., 2016. Estimating the effects of the container revolution on world trade. J. Int. Econ. 98, 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.09.001

Bichou, K., Gray, R., 2004. A logistics and supply chain management approach to port performance measurement. Marit. Policy Manag. 31, 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000174454

Brooks, M.R., Pallis, A.A., 2012. Classics in Port Policy and Management (Books). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Brooks, M.R., Pallis, A.A., 2008. Assessing port governance models: process and performance components. Marit. Policy Manag. 35, 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830802215060

Button, K., 2010. Transport Economics. Edward Elgar.

Carbone, V., Martino, M.D., 2003. The changing role of ports in supply-chain management: an empirical analysis. Marit. Policy Manag. 30, 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000145618

Cariou, P., 2011. Is slow steaming a sustainable means of reducing CO2 emissions from container shipping? Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 16, 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2010.12.005

Chang, Young-Tae ; Kyoung-Suk Choi; Ahhyun Jo; Hyosoo Park. International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics (IJSTL), Vol. 10, No. 1, 2018. Top 50 Authors, Affiliations, and Countries in Maritime Research. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSTL.2018.10007250

Clark, X., Dollar, D., Micco, A., 2004. Port Efficiency, Maritime Transport Costs and Bilateral Trade (NBER Working Paper No. 10353). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Corbett, J.J., Wang, H., Winebrake, J.J., 2009. The effectiveness and costs of speed reductions on emissions from international shipping. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 14, 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2009.08.005

Cudahy, B.J., 2007. Box Boats: How Container Ships Changed the World, 1 edition. ed. Fordham University Press, New York.

Cullinane, K., 2011. International Handbook of Maritime Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Cullinane, K., Khanna, M., 2000. Economies of scale in large containerships: optimal size and geographical implications. J. Transp. Geogr. 8, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(00)00010-7

Cullinane, K., Song, D.-W., 2002. Port privatization policy and practice. Transp. Rev. 22, 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640110042138

Cullinane, K., Wang, T.-F., Song, D.-W., Ji, P., 2006. The technical efficiency of container ports: Comparing data envelopment analysis and stochastic frontier analysis. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 40, 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.07.003

Ducruet, C., Notteboom, T., 2012. The worldwide maritime network of container shipping: spatial structure and regional dynamics. Glob. Netw. 12, 395–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00355.x

Estache, A., González, M., Trujillo, L., 2002. Efficiency Gains from Port Reform and the Potential for Yardstick Competition: Lessons from Mexico. World Dev. 30, 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00129-2

Fugazza, M., Hoffmann, J., 2017. Liner shipping connectivity as determinant of trade. J. Shipp. Trade 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-017-0019-5

Fugazza, M., Hoffmann, J., Razafinombana, R., 2013. Building a Dataset for Bilateral Maritime Connectivity.

Gallup, J.L., Sachs, J.D., Mellinger, A.D., 1999. Geography and Economic Development. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 22, 179–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/016001799761012334

Goss, R.O., 1990. Economic policies and seaports: The economic functions of seaports. Marit. Policy Manag. 17, 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839000000028

Goss, R.O., 1977. Advances in Maritime Economics. CUP Archive.

Grammenos, C.T. (Ed.), 2012. The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business, 2nd ed. Informa Law from Routledge.

Grammenos, C.T. (Ed.), 2002. The Handbook of Maritime Economics and Business. Informa Law.

Haralambides, H.E., 2019, Marit Econ Logist 21: 1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-018-00116-0

Haralambides, H.E 2017, Marit Econ Logist 19: 1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-017-0068-6

Haralambides, H.E., 2008. 10 Years of MEL. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 10, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100199

Haralambides, H.E., 2002. Competition, Excess Capacity, and the Pricing of Port Infrastructure. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 4, 323–347. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100053

Heaver, T., Meersman, H., Moglia, F., Van De Voorde, E., 2000. Do mergers and alliances influence European shipping and port competition? Marit. Policy Manag. 27, 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/030888300416559

Heaver, T., Meersman, H., Van De Voorde, E., 2001. Co-operation and competition in international container transport: strategies for ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 28, 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830110055693

Heaver, T.D., 2002. The Evolving Roles of Shipping Lines in International Logistics. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 4, 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100042

Hoffmann, J., 2012. Corridors of the Sea: An investigation into liner shipping connectivity, in: Les Corridors de Transport, Les Océanides.

Hoffmann, J., 2003. Applying Maritime Economics to Set Foundations for Port and Shipping Policies. Marit. Econ. Logist. 5, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100072

Hoffmann, J., 2002. El costo del transporte internacional, y la integración y competitividad de América Latina y el Caribe.

Hoffmann, J., 2000. El potencial de puertos pivotes en la costa del Pacífico sudamericano. CEPAL.

Hoffmann, J., 1998. Concentration in liner shipping: its causes and impacts for ports and shipping services in developing regions.

Hoffmann, J., Sanchez, R.J., Talley, W.K., 2004. 6. Determinants of Vessel Flag. Res. Transp. Econ., Shipping Economics 12, 173–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0739-8859(04)12006-4

Hoffmann, J., Saeed, N. & Sødal, S. Marit Econ Logist (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-019-00124-8

Hoffmann, J., Wilmsmeier, G., Lun, Y.H.V., 2017. Connecting the world through global shipping networks. J. Shipp. Trade 2, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-017-0020-z

Hummels, D., 2007. Transportation costs and international trade in the second era of globalization. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 131–154.

Hummels, D., 1999. Have international transportation costs declined?

Imai, A., Nishimura, E., Papadimitriou, S., 2001. The dynamic berth allocation problem for a container port. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 35, 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-2615(99)00057-0

Juhel, M.H., 2001. Globalisation, Privatisation and Restructuring of Ports. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 3, 139–174. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijme.9100012

Kaluza, P., Kölzsch, A., Gastner, M.T., Blasius, B., 2010. The complex network of global cargo ship movements. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2009.0495

Kavussanos, M.G., Visvikis, I.D., 2004. Market interactions in returns and volatilities between spot and forward shipping freight markets. J. Bank. Finance 28, 2015–2049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2003.07.004

Kumar, S., Hoffmann, J., 2002. Globalization, The Maritime Nexus. Handb. Marit. Econmics.

Lai, K., Ngai, E.W.T., Cheng, T.C.E., 2002. Measures for evaluating supply chain performance in transport logistics. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 38, 439–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1366-5545(02)00019-4

Langen, P.W. de, 2002. Clustering and performance: the case of maritime clustering in The Netherlands. Marit. Policy Manag. 29, 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830210132605

Langen, P.W. de, Haezendonck, E., 2012. Ports as Clusters of Economic Activity, in: Talley, W.K. (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Maritime Economics. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 638–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444345667.ch31

Lee, C.K.M., Lam, J.S.L., 2012. Managing reverse logistics to enhance sustainability of industrial marketing. Ind. Mark. Manag., Green marketing and its impact on supply chain 41, 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.04.006

Levinson, M., 2008. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger. Princeton University Press.

Li, K.X., Cheng, J., 2007. The determinants of maritime policy. Marit. Policy Manag. 34, 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830701695172

Limão, N., Venables, A.J., 2001. Infrastructure, Geographical Disadvantage, Transport Costs, and Trade. World Bank Econ. Rev. 15, 451–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/15.3.451

Lirn, T.C., Thanopoulou, H.A., Beynon, M.J., Beresford, A.K.C., 2004. An Application of AHP on Transhipment Port Selection: A Global Perspective. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100093

Liu, M., Kronbak, J., 2010. The potential economic viability of using the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as an alternative route between Asia and Europe. J. Transp. Geogr., Tourism and climate change 18, 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.08.004

Mclaughlin, H., McConville, J., Couper, A., Alderton, P.M., Heaver, T., 2013. Reflecting on 40 years of Maritime Policy & Management. Marit. Policy Manag. 40, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2013.782970

McLaughlin, H., Song, D.-W., 2013. Reflections: ‘Looking Back for the Future.’ Marit. Policy Manag. 40, 191–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2013.782965

Meng, Q., Wang, S., 2011. Liner shipping service network design with empty container repositioning. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 47, 695–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2011.02.004

Notteboom *, T.E., Rodrigue, J.-P., 2005. Port regionalization: towards a new phase in port development. Marit. Policy Manag. 32, 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830500139885

Notteboom, T.E., 2006. The Time Factor in Liner Shipping Services. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 8, 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100148

Notteboom, T.E., Vernimmen, B., 2009. The effect of high fuel costs on liner service configuration in container shipping. J. Transp. Geogr. 17, 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.05.003

Notteboom, T.E., Winkelmans, W., 2001. Structural changes in logistics: how will port authorities face the challenge? Marit. Policy Manag. 28, 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830119197

Panayides, P.M., Song, D.-W., 2013. Maritime logistics as an emerging discipline. Marit. Policy Manag. 40, 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2013.782942

Park, R.-K., De, P., 2004. An Alternative Approach to Efficiency Measurement of Seaports. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 6, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100094

Psaraftis, H.N., Kontovas, C.A., 2009. CO2 emission statistics for the world commercial fleet. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 8, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03195150

Radelet, S., Sachs, J.D., 1998. Shipping Costs, Manufactured Exports, and Economic Growth.

Robinson, R., 2002. Ports as elements in value-driven chain systems: the new paradigm. Marit. Policy Manag. 29, 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830210132623

Rodrigue, J.-P., Notteboom, T., 2009. The terminalization of supply chains: reassessing the role of terminals in port/hinterland logistical relationships. Marit. Policy Manag. 36, 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830902861086

Roll, Y., Hayuth, Y., 1993. Port performance comparison applying data envelopment analysis (DEA). Marit. Policy Manag. 20, 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839300000025

Sánchez, R.J., Hoffmann, J., Micco, A., Pizzolitto, G.V., Sgut, M., Wilmsmeier, G., 2003. Port Efficiency and International Trade: Port Efficiency as a Determinant of Maritime Transport Costs. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 5, 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100073

Slack, B., 1985. Containerization, inter-port competition, and port selection. Marit. Policy Manag. 12, 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088838500000043

Slack, B., Comtois, C., McCalla, R., 2002. Strategic alliances in the container shipping industry: a global perspective. Marit. Policy Manag. 29, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830110063694

Slack, B., FRÉMONT, A., 2005. Transformation of port terminal operations: from the local to the global. Transp. Rev. 25, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144164042000206051

Sletmo, G.K., 2001. The End of National Shipping Policy? A Historical Perspective on Shipping Policy in a Global Economy. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 3, 333–350.

Song, D.-W., Dong, J., 2011. Flow balancing-based empty container repositioning in typical shipping service routes. Marit. Econ. Logist. 13, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1057/mel.2010.18

Song, D.-W., 2003. Port co-opetition in concept and practice. Marit. Policy Manag. 30, 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308883032000051612

Stank, T.P., Keller, S.B., Daugherty, P.J., 2001. Supply Chain Collaboration and Logistical Service Performance. J. Bus. Logist. 22, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2001.tb00158.x

Steenken, D., Voß, S., Stahlbock, R., 2004. Container terminal operation and operations research – a classification and literature review. Spectr. 26, 3–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00291-003-0157-z

Stopford, M., 2009. Maritime Economics 3e, 3rd ed. Routledge.

Stopford, M., 2002. Shipping market cycles. Handb. Marit. Econ. Bus. 2, 235–258.

Sys, C., 2009. Is the container liner shipping industry an oligopoly? Transp. Policy, SI: TBGS 16, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2009.08.003

Talley, W.K., 1994. Performance indicators and port performance evaluation – ProQuest. Logist. Transp. Rev. 30.

Tongzon, J., Heng, W., 2005. Port privatization, efficiency and competitiveness: Some empirical evidence from container ports (terminals). Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 39, 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2005.02.001

Tongzon, J.L., 1995. Determinants of port performance and efficiency. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 29, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0965-8564(94)00032-6

UNCTAD, 2017. Review of Maritime Transport 2017, Review of Maritime Transport. UNCTAD, Geneva.

Van Der Horst, M.R., De Langen, P.W., 2008. Coordination in Hinterland Transport Chains: A Major Challenge for the Seaport Community. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 10, 108–129. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100194

Verhoeven, P., 2010. A review of port authority functions: towards a renaissance? Marit. Policy Manag. 37, 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088831003700645

Wang, J.J., Ng, A.K.-Y., Olivier, D., 2004. Port governance in China: a review of policies in an era of internationalizing port management practices. Transp. Policy 11, 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2003.11.003

Williamson, O.E., 2008. Outsourcing: Transaction Cost Economics and Supply Chain Management*. J. Supply Chain Manag. 44, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2008.00051.x

Wilmsmeier, G., Hoffmann, J., 2008. Liner Shipping Connectivity and Port Infrastructure as Determinants of Freight Rates in the Caribbean. Marit. Econ. 38 Logist. 10, 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100195

Wilmsmeier, G., Hoffmann, J., Sanchez, R.J., 2006. The Impact of Port Characteristics on International Maritime Transport Costs. Res. Transp. Econ., Port Economics 16, 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0739-8859(06)16006-0

Endnotes

[1] For further reading on the geography of trade and the role of international transport beyond maritime transport, see Gallup et al. (1999), Limão and Venables (2001), Williamson (2008), Hummels (1999), and Radelet and Sachs (1998).

[2] Some further reading on broader aspects of trade logistics, see for example Lai et al. (2002), Stank et al. (2001), and Steenken et al. (2004). For container networks and logistics see also Meng and Wang (2011), Song and Dong (2011). For transport networks in general and reverse logistics see Lee and Lam (2012).

[3] For further reading on containerization, see the books written for the container’s 50th anniversary Cudahy (2007) and Levinson (2008).

[4] For regular updates and statistics on the participation of different countries in the main maritime businesses, see the UNCTAD RMT Series (http://uncad.org/RMT), the UNCTAD on-line maritime statistics (http://stats.unctad.org/Maritime), and 230 individual maritime country profiles (https://unctadstat.unctad.org/CountryProfile/MaritimeProfile/en-GB/702/index.html).

[5] For further reading on maritime economics and markets see also Panayides and Song (2013), McLaughlin and Song (2013), Mclaughlin et al. (2013), and Haralambides (2008).

[6] For further reading on port issues, see Brooks and Pallis (2012), who provide a selection of “classic” papers on Port Policy and Management. Haralambides (2017) has a nice overview on globalization, public sector reform, and the role of ports in international supply chains.

Brilliant thumbnail sum-up of the maritime research and the follow-up academic publishing.

Still miss your ‘industry impact’ and insights at UNCTAD.

Good luck and regards,

Capt. R. Maitra PhD

LikeLiked by 1 person